Author: Satyapriya Singh

Division of Entomology, ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi - 12, India.

E-mail: satyachintu25@gmail.com

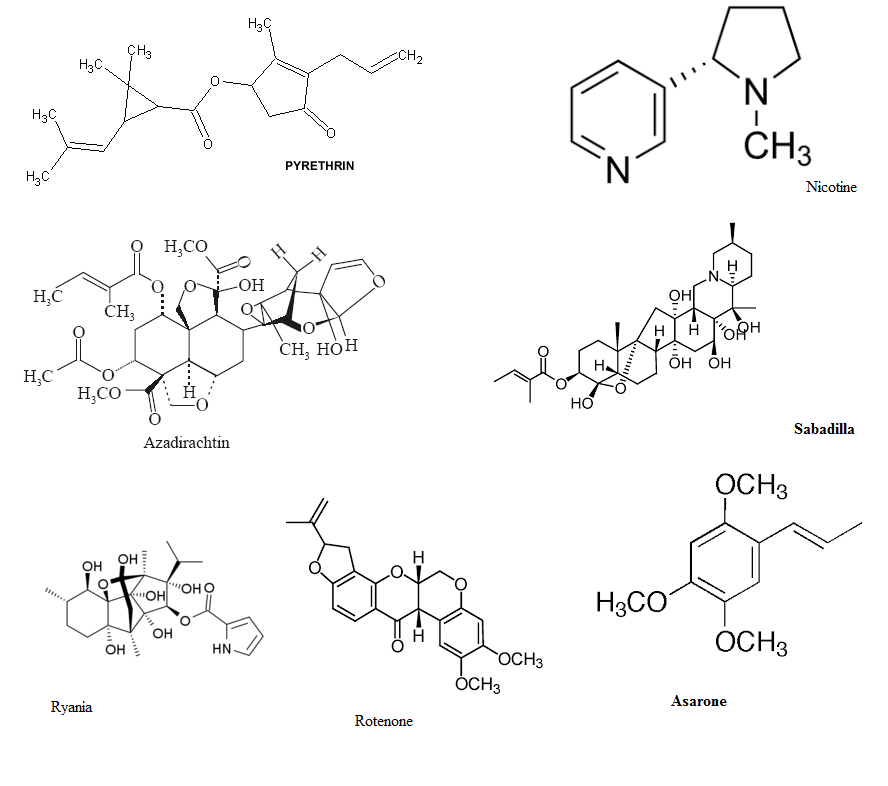

In agricultural pest management, phytochemicals as insecticides are best suited for use in organic food production in industrialized countries but can play a much greater role in the production and postharvest protection of food in developing countries. There is a need for plants that may provide best alternatives to the currently used insect control agents as they constitute a potential source of bioactive molecules. Therefore, there is a great potential for a plant-derived insecticidal compounds. The phytochemicals that have primarily been used and are commercially available include pyrethrin, nicotine, azadirachtin, sabadilla, ryania, rotenone and asarone.

Pyrethrin:

Pyrethrin refers to the oleoresin extracted from the seeds or flower of Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium (Asteraceae). It has a low mammalian toxicity with LD50 1200 to 1,500 mg/kg. It composed three esters of chrysanthemic acid and three esters of pyrethric acid. Among the six esters, those incorporating the alcohol pyrethrolone, namely pyrethrins I and II, are the most abundant and account for most of the insecticidal activity. Pyrethrin is one of the oldest household insecticides still available and is fast acting, providing almost immediate “knockdown” of insects following an application. It works as both contact and stomach poison. The material has a very short residual activity-degrading rapidly under sunlight, air and moisture, so it needs frequent applications. It can be used up until harvest, as there is no waiting interval required between initial application and harvest of food crops (Casida and Quistad, 1995). It kills insects (mode of activity) by disrupting the sodium and potassium ion exchange process in insect nerves and interrupting the normal transmission of nerve impulses. Pyrethrin has activity on wide range of insects and mites, including flies, fleas, beetles, and spider mites.

Nicotine:

Nicotine, which is derived from Nicotiana tabacum, with LD 50 between 50 and 60 mg/kg. It is extremely harmful to humans. Nicotine, a fast-acting nerve toxin, works as a contact poison. It kills insects through bonding to the nerve receptors causing uncontrolled nerve firing, and also by mimicking acetylcholine (Ach) at the neuro-muscular junctions in the central nervous system. It is most effective on soft-bodied insects and mites, including aphids, thrips, leafhoppers, and spider mites.

Azadirachtin :

Azadirachtin is derived from the tree Azadirachta indica, grown in India and Africa. It has an extremely low mammalian toxicity and is least toxic of the commercial botanical insecticides, with a LD50 of 13,000 mg/kg. It is considered as contact poison; however, it has “some” systemic activity in plants when applied to the foliage. The material is generally nontoxic to beneficial insects and mites. Azadirachtin has broad mode of activity, working as a feeding deterrent, insect-growth regulator, repellent, sterilant and oviposition deterrant (Isman, 2006). The material is active on a broad range of insects, including stored grain pests, aphids, caterpillars and Mealybugs.

Sabadilla:

Sabadilla is derived from the seeds of plant Schoenocaulon officinale. It is one of the least toxic botanical insecticides, with mammalian LD50 of 5,000 mg/kg. It works as both contact and stomach poison. Similar to other botanical insecticides, the material has minimal residual activity and degrades rapidly in sunlight and moisture. Sabadilla works by affecting nerve cell membranes, causing loss of nerve function, paralysis, and death. It is effective against caterpillars, leaf hoppers, thrips, stink, and squash bugs.

Ryania:

The bio-active component is derived from the roots and woody stems of the plant Ryania speciosa, native to Trinidad. It has low mammalian toxicity, with a median lethal dose (LD50) of 750mg/kg and has both contact and stomach poison. It has long residual activity. This compound has a unique mode of action and affects muscles by binding to the calcium channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This causes influx of calcium ion in to the cells, and death follows very rapidly. Ryania has better effect on caterpillars. Moreover, it is also active on a wide range of insects and mites, including potato beetle, lace bugs, aphids and squash bug.

Rotenone:

Rotenone is derived from the roots of the two legume plants Lonchocarpus sp. and Derris sp. originally from the East Indies, Malaya and South America. It is a moderately toxic phytochemicals, with a LD50 of 132 mg/kg to mammals. It is also extremely toxic to fish. It works as both contact and stomach poison. Rotenone is slower acting than most other botanical insecticides, taking several days to kill pests; however, pests stop feeding almost immediately. It degrades rapidly in air and sunlight. This bioactive molecule blocks respiration by electron transport on the complex I. It shows broad spectrum of activity on many insects and mite pests, including leaf feeding beetles, caterpillars, lice, mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and fire ants.

Asarone:

Asarone is natural insecticide isolated from Acorus calamus L. This biomolecule is more effective against adults ofSitophilus oryzae, Lasioderma serricorne, and Callosobruchus chinensis and shows both fumigant and contact toxicity.

Structure / Images:

Conclusion:

The phytochemicals used as insecticides are ecofriendly, easily biodegradable, non- or less toxic to non-target organisms and could be produced from locally available raw materials. This potential bio-active component of plant origin could be exploited for the development of novel molecules with highly precise targets for sustainable insect pest management in agricultural ecosystem.

References:

Casida, J. E. and Quistad, G. B. 1995. Pyrethrum flowers: production, chemistry, toxicology and uses. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Isman, M. B. 2006. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annual Review of Entomology. 51: 45–66.

About Author / Additional Info: