Authors: Kumar Rakesh1, D.R. Singh2, Prawin Arya3, Anil kumar4

1Ph. D. Scholar, IARI, New Delhi, 2Senior Scientist, Division of Agricultural Economics, IARI, New Delhi, 3Senior Scientist, IASRI, New Delhi and 4Principal Scientist, IASRI, New Delhi

Introduction

Rajasthan is the largest state in the country and large part of the state is arid or semi-arid and fall under Thar Desert. The climatic conditions are adverse with scarcity of water for irrigation and erratic rains with very low average annual rainfall. These conditions leave a little scope for crop production and enhance the importance of animal husbandry over the crop production especially during recurrent droughts. As per Livestock Census, 2012, the state had a good number of total livestock population (577 lacs) and of the total around 16 per cent were sheep. More than 80 per cent rural families keep livestock in the state. The contribution of animal husbandry sector to the state gross domestic product has been estimated to be around 9 per cent (GoR, 2010). About 35 per cent of the income to small and marginal farmers comes from dairy and animal husbandry in the state. In arid areas the contribution is as high as 50 per cent. Rajasthan ranked third in sheep population and accounted nearly 14 per cent of the total sheep in the country and yielded 35 per cent of the total wool production. Sheep are raised profitably with good employment opportunities in the state with low investment mainly by the economically weaker and socially backward sections (Singh et al., 2006; Suresh, 2008; Kumar et al., 2013). However, the productivity of sheep in India is low as compared to other countries. In addition, the quality of wool produced by Indian sheep is also inferior. The average wool production in India is 0.62 kg per sheep per year and in Rajasthan, it is about 1.12 kg per sheep per year, whereas, it is 4 to 5 kg in Australia and 2.5 kg globally. The consumption of meat has been projected to rise to 8-9 million tonnes by 2020 in which contribution of mutton would be substantial (Birthal and Taneja, 2006). Therefore, the present study was undertaken to examine the temporal and spatial dynamics of sheep production system in Rajasthan.

Material and methods

Sheep are traditionally raised under either stationary or migratory conditions in the state. The migration may be temporary (of short duration to neighboring location) or permanent where flocks spend most of the time on migration usually to long distances. The livestock census-wise data on total sheep and livestock population in Rajasthan state were collected from published sources. The district-wise statistics on sheep population and wool and meat production were also collected. Further, the information on sheep migration in the state were also collected from the publications and website of Department of Animal Husbandry, Government of Rajasthan. To study the temporal and spatial pattern dynamics of sheep population in Rajasthan, the district-wise compound growth rates were calculated over the different time periods related to livestock censuses. For the better interpretation of the district-wise growth in sheep population, the districts were classified into high and low sheep populated districts. The districts, in which sheep density was more (less) than 25 animals per km and share of sheep in total livestock was more (less) than 10 per cent, were considered high (low) sheep populated districts.

Results and discussion

There was an increase in sheep population from 54 lacs in 1951 to 91 lacs in 2012 in the state (Table 1). However, there was almost stagnation in sheep population during 1956 to 1961 and 1966 to 1972 and a deceleration of compound annual growth rate of -5.89 and -5.72 and -4.09 per cent during 1983 to 1988, 1997 to 2003 and 2007 to 2012, respectively. This might be due to severe drought conditions in the state between the above mentioned censuses. The highest growth of 6.47 per cent was observed between 1951 and 1956 censuses and a decline was observed in the successive census. The share of sheep in total livestock was found to be around 20 to 25 per cent. Livestock Census (2012) recorded a decline of 19 per cent in sheep population over the Livestock Census (2007) and also resulted in a decline of sheep share in the total livestock population from 20 to 16 per cent in the state.

Table 1. Trends in sheep population in Rajasthan

| Livestock census | Sheep (No. in lacs) | Share in total livestock population (%) | CGR in sheep population over previous livestock census (%) |

| 1951 | 53.87 | 21.86 | - |

| 1956 | 73.73 | 22.74 | 6.47 |

| 1961 | 73.60 | 21.33 | -0.03 |

| 1966 | 88.06 | 23.50 | 1.09 |

| 1972 | 85.56 | 22.12 | -0.48 |

| 1977 | 99.38 | 24.03 | 3.04 |

| 1983 | 134.31 | 27.05 | 5.15 |

| 1988 | 99.13 | 24.24 | -5.89 |

| 1992 | 121.68 | 25.47 | 5.26 |

| 1997 | 143.12 | 26.33 | 3.30 |

| 2003 | 100.54 | 20.46 | -5.72 |

| 2007 | 111.90 | 19.75 | 2.71 |

| 2012 | 90.80 | 15.73 | -4.09 |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR, 2011

Temporal and spatial dynamics of sheep population in Rajasthan

For the spatial and temporal pattern analysis, all the districts were divided into two groups, viz. high and low sheep populated districts. The high sheep populated districts accounted around 92 per cent of the total sheep population in the state whereas low sheep populated districts accounted only 8 to 9 per cent share in the total population of the state. The districts of western region of the state (Barmer, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, Pali and Bikaner) accounted a lion’s share in the total sheep population. Barmer district had the highest share in the state’s sheep population in the censuses of 2003 and 2007 but growth was found to be highest (10 per cent) in Jaisalmer district. The growth was found to be negative for both categories of districts from census period 1997 to 2003 because of the severe drought conditions in 2002-03.

Table 2. Temporal and spatial dynamics of sheep population in Rajasthan

(Sheep number in lacs)

| District | 2007 | 2003 | 1997 | CGR (%) | ||||

| Sheep | Share (%) | Sheep | Share (%) | Sheep | Share (%) | 2003 to 2007 | 1997 to 2003 | |

| High sheep populated districts | ||||||||

| Barmer | 13.71 | 12.25 | 10.67 | 10.61 | 15.12 | 10.56 | 6.47 | -5.64 |

| Jaisalmer | 13.04 | 11.65 | 8.90 | 8.85 | 12.08 | 8.44 | 10.01 | -4.96 |

| Jodhpur | 9.77 | 8.73 | 8.84 | 8.79 | 15.60 | 10.90 | 2.52 | -9.03 |

| Pali | 9.25 | 8.26 | 8.93 | 8.88 | 13.69 | 9.57 | 0.87 | -6.88 |

| Bikaner | 8.00 | 7.15 | 9.29 | 9.24 | 11.48 | 8.02 | -3.67 | -3.47 |

| Nagaur | 7.96 | 7.11 | 7.47 | 7.43 | 11.72 | 8.19 | 1.59 | -7.23 |

| Jalore | 6.33 | 5.66 | 5.63 | 5.60 | 7.10 | 4.96 | 2.97 | -3.79 |

| Ajmer | 5.02 | 4.49 | 3.93 | 3.91 | 7.14 | 4.99 | 6.32 | -9.48 |

| Churu | 4.52 | 4.04 | 3.81 | 3.79 | 6.42 | 4.49 | 4.38 | -8.34 |

| Bhilwara | 4.33 | 3.87 | 4.47 | 4.44 | 8.45 | 5.91 | -0.77 | -10.09 |

| Ganganagar | 3.80 | 3.39 | 3.39 | 3.37 | 3.51 | 2.45 | 2.88 | -0.57 |

| Jaipur | 3.40 | 3.04 | 3.05 | 3.04 | 3.48 | 2.43 | 2.72 | -2.14 |

| Sikar | 3.19 | 2.85 | 2.37 | 2.36 | 3.06 | 2.14 | 7.71 | -4.17 |

| Hanumangarh | 2.86 | 2.55 | 2.61 | 2.60 | 2.92 | 2.04 | 2.27 | -1.82 |

| Tonk | 2.54 | 2.27 | 2.04 | 2.03 | 3.11 | 2.17 | 5.56 | -6.75 |

| Sirohi | 2.50 | 2.23 | 2.95 | 2.93 | 3.03 | 2.11 | -4.08 | -0.43 |

| Jhunjhunun | 1.90 | 1.70 | 1.63 | 1.62 | 2.23 | 1.56 | 4.02 | -5.12 |

| Rajsamand | 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 2.19 | 1.53 | 1.37 | -9.47 |

| Sub total | 103.38 | 92.38 | 91.19 | 90.90 | 132.32 | 92.45 | 3.18 | -6.02 |

| Low sheep populated districts | ||||||||

| Udaipur | 1.62 | 1.45 | 2.04 | 2.03 | 2.44 | 1.70 | -5.69 | -2.90 |

| Dungarpur | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.43 | 1.00 | -3.74 | -2.37 |

| Alwar | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 1.10 | 0.77 | 2.44 | -3.09 |

| Bharatpur | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 3.83 | -4.08 |

| Chittorgarh | 0.81 | 0.72 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.34 | 0.94 | -6.28 | -4.05 |

| S.Madhopur | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.59 | -0.76 |

| Dausa | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 1.24 | 2.83 |

| Bundi | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.61 | -3.14 | -4.22 |

| Karauli | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 11.05 | -3.52 |

| Kota | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.20 | -3.17 | -2.77 |

| Jhalawar | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.95 | -2.25 |

| Banswara | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.17 | -11.96 | -1.02 |

| Baran | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.13 | -0.59 | -6.29 |

| Dhaulpur | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.09 | -10.47 | -5.05 |

| Sub total | 8.52 | 7.62 | 9.13 | 9.10 | 10.80 | 7.55 | -1.70 | -2.77 |

| Total | 111.90 | 100.00 | 100.54 | 100.00 | 143.12 | 100.00 | 2.71 | -5.72 |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Sheep migration pattern in Rajasthan

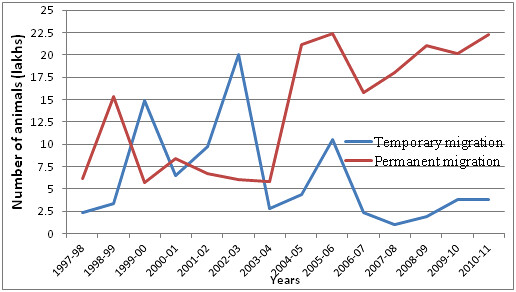

A perusal of Figure 1 shows that there were wide fluctuations in temporary and permanent migration from 1997-98 to 2003-04. However, after 2003-04, an increasing trend in permanent migration and decreasing trend in temporary migration was observed with less fluctuations. The temporary migration was found to be the highest (6.85 lacs) in the triennium average ending (TE) 1999-00 which declined in the successive periods (Table 3). On the other hand, permanent migration was lowest in the same TE 1999-00 which increased in the successive TE periods of 2005-006 and 2011-12. As a result, the overall migratory sheep population showed an increasing trend.

Figure 1: Trends in sheep migration

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Table 3. Sheep migration in Rajasthan

| Migration | Sheep population (in lacs) | ||

| TE 1999-2000 | TE 2005-2006 | TE 2010-2011 | |

| Temporary migration | 6.85 | 5.9 | 3.18 |

| Permanent migration | 9.07 | 16.43 | 21.14 |

| Total migration | 15.92 | 22.33 | 24.32 |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Lack of pasture land, fodder and drinking water and poor market availability at native place forced sheep herders to migrate temporarily or permanently to other locations. However, there was a drastic decline in the growth in temporary migration from 42 per cent during 1997-98 to 2002-03 to negative (-5 per cent) during 2003-04 to 2010-11 (Table 4). However, during the same periods, the reverse was the case of permanent migration. Overall, the growth in total migration declined from 11 per cent during the time period 1997-98 to 2001-02 to 8 per cent during the period 2003-04 to 2010-11. A reflection of the migratory sheep population vis-a-vis the pattern of drought in the state indicated that during drought years, the total sheep migration as well as the proportion of temporary migration recorded sudden increase as observed for the year 2002-03, which was classified as a severe drought year in the state. The major factor responsible for the decline in the temporary migration was the recurrent droughts in the state which forced the flock owners to shift towards permanent migration and to sell large number of animal for livelihood security. These drought conditions also led to increase in the permanent migration in the recent past. However, the variability in the permanent and temporary migration declined during the recent years in comparison to previous period.

Table 4. Growth and instability in sheep migration in Rajasthan

| Migration | Compound annual growth rate (%) | Coefficient of variation (%) | ||

| 1997-98 to 2001-02 | 2003-04 to 2010-11 | 1997-98 to 2001-02 | 2003-04 to 2010-11 | |

| Temporary | 41.93 | -5.22 | 13.89 | 9.5 |

| Permanent | -4.25 | 11.47 | 9.42 | 3.77 |

| Total | 11.45 | 7.94 | 5.82 | 4.02 |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Trends in wool production in Rajasthan

The average wool production in Rajasthan during the period 1990-91 to 2002-03 was found to be 180 lacs kg with 1.77 per cent growth (Table 5). However, during the year 2003-04 to 2009-10, the average wool production was only 145 lacs kg and with a negative growth of around 3 per cent. This reduction in the wool production during this period was due to drastic decline in sheep population on account of 2002-03 and 2008-09 droughts. Further, the average wool production was around 132 lacs kg during 2010-11 to 2013-14.

Table 5. Average wool production in Rajasthan

| Period | Average production (in lacs kg) | CGR (%) |

| 1990-91 to 2002-03 (13 years) | 180.04 | 1.77 |

| 2003-04 to 2009-10 (8 years) | 145.28 | -3.02 |

| 2010-11 to 2013-14 (3 years) | 131.60 | - |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

A district wise and temporal analysis showed that the average wool production was highest in Barmer and Bikaner districts in TE 2005-06 and 2009-10, respectively (Table 6). The contribution of Ajmer district was around 3.40 lacs kg in TE 2005-06 and increased to 5.62 lacs kg in TE 2009-10 with the highest growth of around 9 per cent in the state. Whereas in most of the high sheep populated districts, it was found to be decelerating. The highest decline (11 per cent) was observed in Churu district. On the other hand, in low sheep populated districts, Udaipur district showed impressive growth of around 17 per cent in wool production. The overall decline in the growth of wool (-3 per cent) was found in Rajasthan. This shows how the decline in the sheep population led to a large decline in the wool production.

Table 6. District-wise average wool production in Rajasthan

(in 000’ kg)

| Districts | Average wool production | |||

| TE 2005-06 | TE 2009-10 | CGR (%) | ||

| High sheep populated districts | ||||

| Ajmer | 339.67 | 561.67 | 9.35 | |

| Barmer | 1657.33 | 1294.33 | -4.12 | |

| Bhilwara | 628.67 | 495.00 | -5.02 | |

| Bikaner | 1589.67 | 1654.00 | 0.39 | |

| Churu | 714.33 | 430.00 | -11.54 | |

| Ganganagar | 593.33 | 643.00 | 0.47 | |

| Hanumangarh | 418.00 | 424.33 | -1.50 | |

| Jaipur | 352.33 | 275.00 | -9.51 | |

| Jaisalmer | 1604.67 | 1578.67 | -0.39 | |

| Jalore | 935.67 | 806.67 | -4.71 | |

| Jodhpur | 1414.67 | 948.67 | -8.89 | |

| Nagaur | 1246.00 | 827.33 | -9.46 | |

| Pali | 1525.33 | 1397.33 | -3.06 | |

| Sikar | 346.67 | 259.33 | -6.46 | |

| Tonk | 283.33 | 232.00 | -6.17 | |

| Sirohi |

| 250.33 | 0.50 | |

| Jhunjhunu | 281.33 | 162.67 | -13.01 | |

| Low sheep populated district | ||||

| Udaipur | 158.00 | 304.00 | 17.26 | |

| Others | 1031.33 | 1257.67 | 0.36 | |

| Rajasthan | 15120.33 | 13551.67 | -3.03 | |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Sheep meat production

The total meat production in the state was 92 thousand tonnes in 2009-10 in which 14 thousand tonnes of meat were contributed by the sheep with a share of around 16 per cent (Table 7). The result also showed that there was poor growth of only 2 per cent per year in sheep meat as compared to total meat production (6 per cent). The share of mutton was more or less remains around 20 to 26 per cent of the total meat production in the state. In recent years, the growth in sheep meat production was found to be moderate and resulted in decreased share of mutton in total meat production in the state. This is important to note that there is huge demand of sheep meat in international market. Indian diet is also diversifying and now more population are opting non-vegetarian food. Hence, the domestic demands for meat, fruits and vegetables are increasing in the country. The consumption of meat has been projected to rise to 8-9 million tonnes by 2020 in which contribution of mutton would be substantial (Birthal and Taneja, 2006). Further, the demand for vegetables was projected to be high in the future (Sivaramane et al. 2009). To multinational and domestic markets, however

Table 7. Sheep meat production in Rajasthan

(In 000' tonnes)

| Year | Sheep meat | Other meat | Total meat | Sheep share in total meat (%) |

| 2000-01 | 12.0 | 39.1 | 51.1 | 23.5 |

| 2001-02 | 13.7 | 42.6 | 56.3 | 24.4 |

| 2002-03 | 13.9 | 44.7 | 58.6 | 23.7 |

| 2003-04 | 16.2 | 46.7 | 62.9 | 25.8 |

| 2004-05 | 14.5 | 49.8 | 64.3 | 22.5 |

| 2005-06 | 14.9 | 52.9 | 67.8 | 22.0 |

| 2006-07 | 16.0 | 53.4 | 69.4 | 23.0 |

| 2007-08 | 16.2 | 54.6 | 70.8 | 22.9 |

| 2008-09 | 16.2 | 67.7 | 83.8 | 19.3 |

| 2009-10 | 14.3 | 77.7 | 92.0 | 15.5 |

| CGR (%) | 2.13 | 6.82 | 5.85 |

Source: Department of animal husbandry, GoR (2011)

Summary and conclusions

Although, sheep population increased impressively in Rajasthan since independence, there was a decreasing trend in the recent past. There was also a decline in almost all the districts in recent past. The decline in the sheep and wool production was related to the drought conditions in the state. Sheep migration did not show any definite trend and was highly unstable in the state. However, there was a declining trend in the temporary migration and increasing trend in permanent migration. Increase in permanent migration in recent time may be related to increased variability in the climatic factors. Although, the state ranked first in the wool production in the country, the average wool production is declining. The district-wise wool production also showed decreasing trend in most of the high sheep populated districts. The fall in wool production was partly due to decrease in sheep population on account of more sale of animal for livelihood security during drought years. Secondly, the farmers are not interested for better management of wool production on account of meagre contribution of wool in total income realization. There is huge demand of sheep meat in international and domestic markets, however the growth in sheep meat production was found to be moderate in the state. Therefore, to sustain the livelihood security to the poor sections of the society, efforts should be undertaken to stabilise sheep production system in the state. Subsidised fodder and feed may be provided during severe drought conditions. Effective and subsidised credit through Kisan Credit Card can be evolved for sheep owners like crop loan to arrest the distress sale of animals. The market imperfection and poor infrastructure are the major impediments in the realization of full economic potential of this production system. Therefore, urgent attention is needed for development of processing facilities and reform the small ruminant markets in the state.

References:

1. Bhatia, J., U.K. Pandey and K.S. Suhag (2005). Small Ruminant Economy of Semi- arid region of Haryana, Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 60(2): 163-83.

2. Birthal, P.S. and V.K. Taneja (2006). Livestock sector in India: Opportunities and challenges for small holders. Paper presented at the International Workshop on Smallholder Livestock Production in India: Opportunities and Challenges, ICAR, ILRI and NCAP. 31 Jan-1Feb, New Delhi.

3. GoI (2012). Report of the working group on Animal Husbandry and Dairying for the eleventh five year plan (2012-2017), Planning commission, Government of India, New Delhi, p 128.

4. GoI (2014). 19th Livestock Census-2012, All India Report, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries, Government of India, New Delhi, p 120.

5. GoR (2010). State Livestock Development Policy, Department of Animal Husbandry, Government of Rajasthan, Jaipur, p. 23.

6. GoR (2011). Prasasnik Prathivedan. (2010-2011). Department of Animal Husbandry, Jaipur.

7. Kumar, S., R. Kumar, D. R Singh, Anil Kumar, Prawin Arya and K. R. Chaudhary (2013), “Equity, efficiency and profitability of migratory sheep production system in Rajasthan”, Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 83(9): 976�"982.

8. Singh D R, Sushila Kaul and Sivaramane N. (2006). Migratory sheep and goat production system: the mainstay of tribal hill economy in Himachal Pradesh, Agricultural Economics Research Review, 19(1): 387�"98.

9. Sivaramane, N., Singh, D.R. and Arya, Prawin 2009. An econometric analysis of household demand for major vegetables in India, Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, 23(1): 66-76.

10. Suresh, A., D.C. Gupta and J.S. Mann (2008). Returns and economic efficiency of sheep farming in semi-arid regions: A study in Rajasthan. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev., 21(2): 227-234.

About Author / Additional Info:

Sr. Scientist, Division of Forecasting and Agricultural Systems Modelling, IASRI, New Delhi.