Authors: Mahajan Mahesh Mohanrao1 (mahimm1@gmail.com), Pawan S. Mainkar1, Dushyant Pratap Singh2, Kanika2

1 Division of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, IARI, New Delhi-110012

2 National Research Centre on Plant Biotechnology, IARI, New Delhi-110012

Microbes are so small that we can't see them by our naked eyes but they are having immense potential. Natural environments harbour a large diversity of microorganisms estimated to be 1030 (Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2008) out of which prokaryotes account for about 106 to 108 different genospecies. Most of them have not yet been identified or characterized as yet (Sleator et al., 2008). The microbial diversity is in-exhaustive and microbial community represents the largest reservoir of undescribed biodiversity (Nichols, 2002). Only a small fraction 0.1 to 1% of all kind of microorganisms present in environment can be cultured by employing traditional or conventional laboratory methods, remaining ~99% of microbes are not culturable (Amann et al., 1995). Extreme environments are a major source of potentially significant but untapped microbial diversity for potential use as resources for biotechnological processes and products. The genomes of many uncultured and unculturable species encode a largely unexplored reservoir of novel genes and metabolic capabilities.

Conventional sequencing involves culturing of identical cells as a source of DNA. However, studies revealed that there are probably large groups of microorganisms in many environments that cannot be cultured and therefore cannot be sequenced. To overcome the problems and limitations associated with culture dependent techniques, the community genomes (metagenome) of mixed microbial communities from environmental niches can be extracted and exploited by an approach called metagenomics (Handelsman et al., 1998). Methods based on 16S rRNA gene analysis through advanced molecular biology techniques such as PCR, cloning and sequencing approaches provide extensive information about the taxa and species present in an environment. These molecular techniques have improved our understanding of microbial diversity and ecology (DeLong, 2005). These studies focused on 16S ribosomal RNA sequences which are relatively short sequences, often conserved within a species but generally different between species. It has been found that many 16S rRNA sequences do not show homology with any known cultured microorganism, indicating that there are numerous non-isolated organisms present in the environment. Metagenomic studies, a culture independent approach allows identification of not only culturable but also unculturable undescribed bacteria (Petrosino et al., 2009). Metagenomics bypasses the need for isolation or cultivation of microorganisms.

Pace et al., (1985) were the first to propose the direct cloning of environmental DNA, using this approach Schmidt et al., (1991) cloned DNA from picoplankton in a phage vector for 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses. The first successful screening of metagenomic libraries on the basis of function was achieved by Healy et al., (1995). DNA isolation, especially from extreme environments, is still a technological challenge. Nevertheless, significant progress has been made and various protocols for the isolation of high quality DNA from a variety of environments, i.e., soil, marine picoplankton, contaminated subsurface sediments, groundwater, hot springs and surface water from rivers, glacier ice, Antarctic desert soil, and buffalo rumens have been standardized (Rhee et al., 2005).

The 16S rRNA gene is highly conserved between different species of bacteria and it also has variable region (V1-V9) which can be amplified to determine microbial diversity and hence used for phylogenetic studies. 16S rRNA gene based analysis was utilized to study bacterial diversity inhabiting different environmental niches (Kim et al., 2010; Shivaji et al., 2010).

Direct access to the genomic DNA of microbial community can help to understand lifestyle, evolution and diversity of the microorganisms and expose more of the hidden world of microbes (Krause et al., 2008). The use of metagenomics combined with next generation sequencing offers the ability to rapidly identify, characterize and understand microbial communities in detail (Liu, 2008). The recently launched GS-FLX-titanium sequencer based on pyrosequencing allows quick and inexpensive analysis of microbial diversity in different samples in a single run without the need of cloning (Liu et al., 2008).

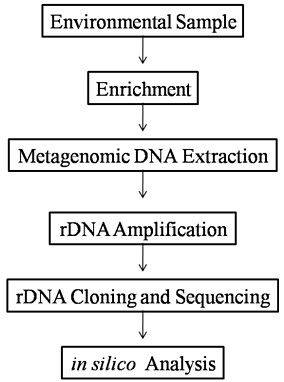

Fig: The general flow chart for characterization of environmental samples:

References:

1. Amann R I, Ludwig W, and Schleifer K H. (1995) Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59: 143â€"169.

2. DeLong E F. (2005) Microbial community genomics in the ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 459-469.

3. Handelsman J, Rondon M R, Brady S F, Clardy J, Goodman R M. (1998) Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chem. Biol. 5: 245â€"249.

4. Healy F G, Ray R M, Aldrich H C, Wilkie A C, Shanmugam K T. (1995) Direct isolation of functional genes encoding cellulases from the microbial consortia in a thermophilic, anaerobic digester maintained on lignocellulose. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43: 667â€"674.

5. Kim E H, Cho K H, Lee Y M, Yim J H, Lee H K, Cho J C, Hong S G. (2010) Diversity of cold-active protease-producing bacteria from arctic terrestrial and marine environments revealed by enrichment culture. J. Microbiol. 48: 426-432.

6. Krause L, Diaz N N, Goesmann Z, Scott K S, Nattkemper T W, Rohwer F, Edwards R, Stoye J. (2008) Phylogenetic classification of short environmental DNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: 2230-2239.

7. Liu Z, DeSantis T Z, Andersen G L, Knight R. (2008) Accurate taxonomy assignments from 16S rRNA sequences produced by highly parallel pyrosequencers. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: 120.

8. Nichols D S, Sanderson K, Buia A, Kamp J, Halloway P, Bowman J P, Smith M, Mancuso C, Nichols P D, McMeekin T A. (2002) Bioprospecting and biotechnology in Antarctica. In: Jabour G J, Haward M (eds). The Antarctic: past, present and future. Antarctic CRC. Res. Report Hobart. 28: 85-103.

9. Pace N R, Stahl D J, Lane D J, Olsen G J. (1985) Analyzing natural microbial populations by rRNA sequences. ASM News. 51: 4â€"12.

10. Petrosino J F, Highlander S, Luna R A, Gibbs R A, Versalovic J. (2009) Metagenomic pyrosequencing and microbial identification. Clin. Chem. 55: 856-866.

11. Rhee J K, Ahn D G, Kim Y G, Oh J W. (2005) New thermophilic and thermostable esterase with sequence similarity to the hormone-sensitive lipase family, cloned from a metagenomic library. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 817â€"825.

12. Schmidt T M, DeLong E F, Pace N R. (1991) Analysis of a marine picoplankton community by 16S rRNA gene cloning and sequencing. J. Bacteriol. 173: 4371â€"4378.

13. Shivaji S, Pratibha M S, Sailaja B, Hara K K, Singh A K, Begum Z, Anarasi U, Prabagaran S R, Reddy G S, Srinivas T N. (2010) Bacterial diversity of soil in the vicinity of Pindari glacier, Himalayan mountain ranges, India, using culturable bacteria and soil 16S rRNA gene clones. Extremophiles. 15: 1-22.

14. Sleator R D, Shortall C, Hill C. (2008) Metagenomics. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 47: 361â€"366.

15. Turnbaugh P J, Gordon J I. (2008) An invitation to the marriage of metagenomics and metabolomics. Cell. 134: 708â€"713.

About Author / Additional Info:

Ph.D. scholar, Worked on Metagenomics during Masters and now working on Wheat for salinity tolerance.